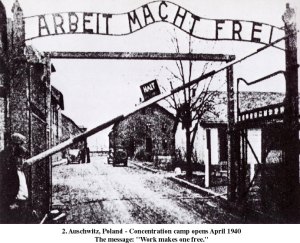

“A week after we got there they started transporting people out of the ghetto. They picked a certain number of families each time to transport to Auschwitz. We didn’t know where we were going at the time – we just knew we were going to a labor camp“… Only the First Four Hurt: Part II.

The following is Part III in an ongoing series documenting my Uncle Irving’s account of his personal and family history during and after the Holocaust. Prior entries include Only the First Four Hurt and Only the First Four Hurt: Part II. . . slf

“We were among the first transports. About a hundred of us were forced into a train car with two sliding doors. Space was so tight we could only stand and there was no toilet for us. The Germans put a bucket in the train to be used by everyone. So if you had to go, it was in front of everyone in this bucket.

“We traveled like that for two or three days – I’m not really sure how long. It was April so it wasn’t really hot but on a sunny day on the train it could be. We passed through towns where we’d stop to wait for other trains to pass. I remember people watching us – town people – and everybody on the train was screaming for water. We were so thirsty. There was no food or water.

“We got to the final destination which was Auschwitz but at the time I didn’t know what it was or where I was. Germans were there with whips and dogs and they were yelling and screaming for us to ‘Rush! Rush! Rush!’ to get off the train and go stand in line.

“I was with my two youngest brothers and my mother and father – there were only three of us kids at home at the time. My four older siblings had moved to Budapest to stay with family and get an education. I remember my father was holding my youngest brother Deszo’s hand and my mother was holding my other brother Gyorge’s arm. He was about three or four years old.

“When the Germans formed lines, they separated me from them. Now I know it’s because I looked older. My relatives in Budapest were rich and they owned clothing stores and they had sent us clothing to hide. The anti-Jewish laws were affecting all Hungarian Jews, even in Budapest. So they sent men’s suits to our house for us to hide in case their stores were taken away from them. At 15, I had dressed in a man’s suit before leaving home; never in my life had I ever worn a suit like that.

“Because I was dressed in that suit I looked older and I was sent to the line for people going to the work camp. My family was separated into the other line and sent to the crematorium. But at the time, I didn’t know where my family was going.

“They took us into Auschwitz into a camp where we got undressed and went to take a shower. We had to undress completely and get our heads shaved and then we were issued our pajamas. They were like striped overalls.

“The kapos in the camp weren’t German – only Polish – and I didn’t speak anything other than Hungarian. So I asked them when I would see my parents and they pointed to the sky. We were so scared at the time that I don’t remember understanding what that meant. I couldn’t think about it. I was scared and shaking. It all happened very fast.

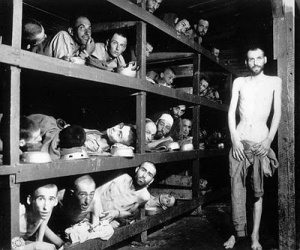

“On the first day I was taken to a barracks and there were hundreds of people inside. But there were no children around. And if there were, they were kept alive for medical experiments. They didn’t leave any kids alive that they didn’t want to use for something.

“Each barrack had a Schreiber and a kapo. A schreiber (literal translation from German: “scribe”..slf) keeps records and the kapo carries out Nazi orders. These people weren’t Jewish. They were Polish or from some other country the Nazis took over. Usually they were criminals who had been given authority. Some of them were homosexual and although I didn’t know it at the time, a few kids were spared for each barracks for the kapo and schreiber to….

Irving trailed off at this point and looked down at his hands, resting folded on the dining room table. He resumed a moment later.

“When we got out of the wagons at the barracks and were being rounded up with whips and dogs and they yelled ‘run!’ and go here or there, 99% of the kids were gone. Teenagers, like me, were beyond kid status.

“I remember the first night. We fell asleep on bunk style slots that ran three to four levels high. We were so tired from standing on the train for days that as soon as we got our clothes and went in, we went to sleep.

“The next day they gave each of us a container to be filled with soup once a day. I didn’t want to look at the soup let alone eat it. It wasn’t soup. It was grass mixed with water. I refused to eat mine that day and some of the people who had already been there for a bit were more than happy to take it from me. They said: ‘By tomorrow you’ll be hungry enough to eat it.’ Sure enough, after 2-3 days of not eating, I ate.

I was curious: Did he see anyone from home? Did he recognize anyone?