This is the fifth part in a series documenting my Uncle Irving’s account of his personal and family history during and after the Holocaust. Previous entries include Only the First Four Hurt , Only the First Four Hurt: Part II, Only the First Four Hurt: Part III and Only the First Four Hurt: Part IV..slf

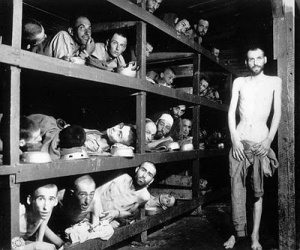

We had bunks and I don’t remember who was next to me or who was my neighbor. We were all in our private worlds. Trying to survive. That’s what we thought about all day long.

I remember one guy who was with me in Auschwitz from the town I came from. I didn’t even know he was there in the camp. But he must’ve known that I was there because one day — we each got a small piece of bread every day to eat. It wasn’t really bread. It was made of sawdust. Every person got half a loaf of those sawdust breads every day – A few months into being in the camp this man from my town came to me with half a loaf and said: ‘Take this. I can’t eat anymore. Maybe it’ll help you.’ Maybe he knew something I didn’t. I never saw him again.

There are a lot of things you try to push away.

Irving’s face crumbled. He bowed his head and with shoulders heaving with sobs, he divulged:

All these years I tried to black all this out. For me it was natural. That’s why I’m breaking down now. For me it was always natural.

He continued sobbing quietly. And then he wiped his face with one of the white, paper napkins on the table and pressed on:

Things continued like that until February 1945. The Russians were coming close to the camp. Of course we didn’t know that. But the Germans decided to clear out the camp and sent us marching. I don’t know how many days we marched in the snow and rain without food. But if anyone fell, they were shot dead on the spot.

Irving was referring to the death marches. As Russian troops advanced from the East and U.S./British troops approached from the West, a panicked German army attempted to clear out concentration camps and “erase evidence” of the atrocities committed within by marching camp prisoners to remote locations. Lacking food, water or insulation from the freezing cold, scores of already weakened and ill prisoners died en route.

After walking many days without food or water we got to a camp. It wasn’t a camp but that’s what they called it. It was a forest called Gunzkrhin. And I remember that when we walked into this forest area, dead bodies were piled one on top of each other as high as a building.

I fainted. And from that point I don’t remember any more until…I have no idea how long I was unconscious but it must have been a very long time. The next thing I remember is that one day the army – the SS army – came in and they were passing out food. Gift packages to everybody with drinks and food and bread and chocolate and I don’t remember what else.

Nobody could believe they were doing that. We thought they just wanted to bribe us before killing us. The Red Cross came in the same day to see how they were treating the prisoners. Then it was clear why they were feeding us.

I don’t remember if I ate anything but I lost consciousness again. I do remember that whoever stayed alive….

Irving trailed off here…crying quietly.

Most people died. There were only a few hundred of us left that were even able to move anymore.

The next thing I remember is that the Germans disappeared. People were laughing and screaming, saying that the Americans had come. I was in and out of consciousness. But I remember them yelling and screaming that the Americans had liberated us.

The Americans were passing out food and feeding people. But whoever ate dropped dead. I wasn’t strong enough to eat or get up onto my feet. I guess I was just lying on the ground. I was lucky.

When liberating concentration camp survivors, unknowing soldiers offered food to the starving victims. The sudden onslaught of solid nourishment was such an overwhelming shock to survivors’ systems that many died of “food overdose”.

I remember the American soldiers had taken SS as P.O.W.’s and they were helping to feed us. After people died from the food, they sent SS people with porridge and very light food to eat. I was there for two days.

Then I was taken to a sanitorium in Lindz, Austria at an American army camp. I was unconscious and I woke up in the sanitorium a month or maybe a few weeks later. I don’t have an exact recollection of time but at the beginning May or something similar, they took me to a recovery place. That’s when I got my mental faculties and consciousness back… he indicated, tapping his head.

We were there until they got ready to send people who had stayed alive off to different places.

Some of the long time of blackout from the time I was in the field to the time I was taken to the sanitorium I was unconscious. Sometimes today I try to remember things like the day before the Red Cross visited us when the Germans gave us those nice things. I also try not to remember other things.

But there must have been a time lapse from the time the SS left the forest to when the Americans came in. I’ll tell you why: I was weak but I left the camp with one of the boys and found a dead horse in the town where normal Germans lived. We decided to cook the head for ourselves. I remember this and the horse very clearly but then I don’t remember all of it. Maybe it was a delirious nightmare.

Off to the side, my Aunt Babe had been listening. She signaled and shook her head ‘no’. “Hallucination” she said, looking at Irving. “There’s no way you would have had the strength to go into town and get a horse and cook it.”

In deference to 5 high school years spent in Mr. Hayden’s basic and advanced French classes, I was able to decipher that: 1) Lisa was being invited to a journalism awards ceremony 2) The ceremony would take place in Monaco, and 3) Bleedin’

In deference to 5 high school years spent in Mr. Hayden’s basic and advanced French classes, I was able to decipher that: 1) Lisa was being invited to a journalism awards ceremony 2) The ceremony would take place in Monaco, and 3) Bleedin’