This is the fourth part in a series documenting my Uncle Irving’s account of his personal and family history during and after the Holocaust. Previous entries include Only the First Four Hurt , Only the First Four Hurt: Part II and Only the First Four Hurt: Part III...slf

My Uncle Irving has a habit. When he tells a story he sometimes breaks into a wide grin. And a slight chuckle. His narration continues but within seconds his face goes distorted, his voice cracks and he breaks down into sobs while delivering some sordid twist to the tale he is telling. At this point, the narration stops and he hangs his head, shoulders heaving with sobs. This is a habit I witnessed numerous times while documenting his story…slf

**********

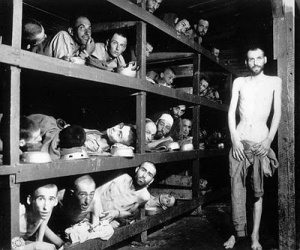

After Mauthausen I was taken to another camp – Gusen II. This was a real work camp. A camp where people were sent to different kinds of factories and were given jobs. It was very serious. First they took me to – I have no idea what the factory was but it was underground and there were real big pieces of wood – trees – that we had to move from one place to another. They brought them in with trucks and we had to move them.

One time a big piece of lumber fell off the truck and I got hit by it, I think in the head, and fell over. After that they decided I was too weak to do that work anymore. So they took me to a place where we had to fill up small wagons the size of cars with broken stones. The wagons sat on train tracks. Somebody would push the cars away and when they brought back the empties we’d fill them again. What they did with it I have no idea.

Between all these things, something happened every day. People got killed, people got close to the fence and were shot or electrocuted, people committed suicide by throwing themselves onto the electric fence.

Something, indeed, happened every day at the Gusen Camps. Gusen I, II and III, three of 49 Mauthausen, Austria sub-Camps, came to be recognized as particularly tortuous. “Compared to Gusen,” one historian commented “the other camps were paradise.” Scores of children in Gusen were “euthanized” by lethal injection to the heart and the elderly and ill were put to painful, slow death by being forced underneath pummeling, freezing cold shower water in freezing cold temperatures. The main focus of Gusen labor centered around mining stone quarries.

The inmates’ nickname for Gusen II: “The Hell of hells”

I remember it was very snowy and cold. That was winter. We would stand out there for hours in our pajamas and wait for them to count us. And people got beaten up for all kinds of reasons.

I had no friends. No people I talked with or anything like that. It didn’t work that way. We were all trapped in our own private worlds. Everybody was out to save his own life and to survive. There are a lot of things I didn’t tell you because I wanted to block them out. There are so many stories that I could tell you….

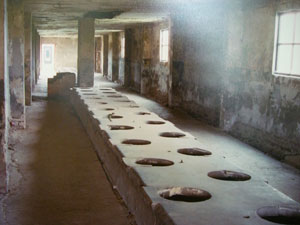

In Guzen II they had a latrine for the whole camp. For everyone. It was a long toilet where you sit on a wooden plank that has holes. You sit there to do what you need to do. It was walking distance from the barracks – a 5-10-minute walk.

One night in middle of night – I didn’t know it but they knew it. I guess I was sort of sleep walking .. I went to make pee pee and I couldn’t make it. So I must have made in my pants.

The next day, they called me – the Kapo to the Schreiber’s office at the end of the barracks. I didn’t understand the language. But they had decided I would get 24 lashes with a stick. I asked: “For what? What did I do?” It was because I made in my pants in the middle of the night. And I didn’t even know I had done it.

The next day, they called me – the Kapo to the Schreiber’s office at the end of the barracks. I didn’t understand the language. But they had decided I would get 24 lashes with a stick. I asked: “For what? What did I do?” It was because I made in my pants in the middle of the night. And I didn’t even know I had done it.

In case you ever have to get 24 lashes with a stick….

my Uncle looked me straight in the eye and then grinned and chuckled. It was his habit.

Only the first four hurt. After that you feel nothing. I fainted.

His head bowed and shoulders heaving with sobs, he paused for a few minutes. His sobs audible, he wiped at streaming tears with a table napkin. A few minutes later, he resumed.