This past Holocaust Day I stood with head bowed during the moment of silence, attempting to contain the flood of emotions that washes over me each year when the sirens sound. But this time as the wailing powered down, I had an epiphany: It’s time to get Uncle Irving’s history.

Uncle Irving is married to my dad’s sister Esther or Aunt Babe. It’s been her nickname since childhood. Growing up in Cincinnati, my Aunt Babe, Uncle Irving and my four first cousins were fixtures in my life: We dined together at our house on the Jewish holidays, BBQ’d and played badminton on the lawn of theirs on July 4th, the cousins and I went to the same sleep-away camp each year and we attended the same youth group.

When I needed information or immediate advice while both parents were at work it was Aunt Babe I phoned in search of answers. For new gym shoes, socks or underwear it was off to the downtown warehouse Uncle Irving worked in & up to the top floor inside the creaky freight elevator to take my pick from multiple boxes and shelves of assorted wear-ables.

Whenever holiday dinners rolled around, though, my siblings and I were instructed prior to guest arrival: “Put the dog in the laundry room. Uncle Irving is coming over.”

We had been briefed numerous times: Uncle Irving, a Holocaust survivor, was frightened of dogs. The Nazis had used German Shepherds to instill fear or attack Jews in the ghettos and camps. And although we didn’t have Shepherds – ours were small Boston Terriers – we had to enclose them regardless.

Uncle Irving had a whole bunch of “isms”. He was super careful about the food he ingested, the utensils he used and the venues in which he was willing to eat. He had a habit of inspecting all three for a measure of cleanliness only he could grade. He would wake up at 4 a.m., his family joked, in order to arrive at the bakery doors prior to the 5 a.m. opening. He wanted to buy his rolls fresh from the oven before anyone else had a chance to touch them.

Our mother told us his food “isms” were a result of camp survivors being forced to use the same container for receiving doled out “meals” as for collecting personal waste.

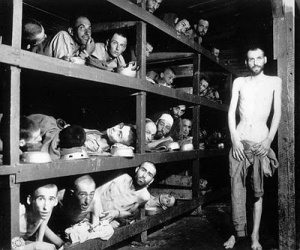

That’s what our Mom told us. Our parents also shared that both of Uncle Irving’s parents and several of his siblings had been gassed to death at Auschwitz. And we knew he hailed from Hungary.

But I never confirmed any of the stories with Uncle Irving himself. Except for his Hungarian roots which was an obvious personal characteristic because he spoke Hungarian with his brother and sisters whenever they were together.

The truth is, decade after decade, nobody, including his wife and children, confirmed anything about the years he spent in the ghettos, concentration camps and hiding out in the forests. His kids and Aunt Babe knew he’d been through tremendous trauma but the unspoken rule was that he didn’t talk about his past.

And no one dared trespass into that realm.

As years passed and he moved to Israel with Aunt Babe to be closer to three of his four children and the grandchildren, the silent oath remained in place. Even when his grandchildren worked on obligatory family tree school projects necessitating interviewing and digging, information regarding his past had to be gleaned from Babe.

But something shifted after Uncle Irving suffered a sudden bout of agoraphobia in his 60’s that kept him house-bound for a year. Agoraphobia, I discovered while writing a story about 2nd Generation Holocaust Survivors, is common among survivors who have internally buried their trauma.

When he was able to leave the house again, he began disclosing bits of information about the past. Seated at a dinner gathering, someone’s comment or remark would spark a personal story. The family, starved of information thus far, would sit in silence absorbing the revelations. Or, upon discovering that a new acquaintance had also been in the camps, he would swap information in the presence of Aunt Babe or other family members.

The instances were random, unprovoked and family members were stunned but grateful when they occurred. But they were the stirrings of something looming larger and as I stood with head bowed last April, it occurred to me that as a non-immediate, once-removed family member and a person who routinely interviews others for a living, maybe my uncle would talk to me. I knew it was important to document his story and I also felt that this was something I could do for him and his family to repay them for their generosity and kindness throughout the years.

I live in Tel Aviv, about twenty minutes from Aunt Babe and Uncle Irving’s place. In recent years I have been through some taxing personal times and Uncle Irving, Aunt Babe and my cousins have been staunch allies providing refuge, advice, legal counsel, love & faith. Uncle Irving even put up his house as equity on my behalf in a time of need.

And so I approached him with my proposition: Can I come over and document your personal history?

And he agreed.

I spent several sessions talking with him, asking questions, probing and typing. The sessions were not comfortable and he warned in advance that he would cry. And he did. At times he sobbed heavily into dining room table napkins. I offered to stop saying I could come back another time. But he wanted to continue.

In the coming blog entries I will share Uncle Irving’s story because I believe that re-telling his history is as important as the documentation itself. As I share, the above title will become clear.

In deference to 5 high school years spent in Mr. Hayden’s basic and advanced French classes, I was able to decipher that: 1) Lisa was being invited to a journalism awards ceremony 2) The ceremony would take place in Monaco, and 3) Bleedin’

In deference to 5 high school years spent in Mr. Hayden’s basic and advanced French classes, I was able to decipher that: 1) Lisa was being invited to a journalism awards ceremony 2) The ceremony would take place in Monaco, and 3) Bleedin’